The Tree, the Serpent, and the Titans Pt. 1

The Tree, the Serpent, and the Titans

- from The Hermetic Tradition by Julius Evola

One of the symbols that we encounter in diverse traditions remote in both time and space is that of the tree. Metaphysically, the tree expresses the universal force that spreads out in manifestation the same way that the plant energy spreads out from its invisible roots to the trunk, branches, leaves, and fruit. Consistently associated with the tree are on the one hand, ideas of immortality and supernatural consciousness, and on the other, symbols of mortal, destructive forces and frightening natures such as dragons, serpents, or demons. There also exists a whole cycle of mythological references to dramatic events in which the tree plays a central part and in whose allegory profound meanings are hidden. The biblical myth of the fall of Adam, among others, is well known. Let us highlight some of its variants, but not without first pointing out the universality of the symbolical elements of which it is composed.

In the Vedas and Upanishads we find the "world tree," inverted sometimes to suggest the origin of its power in "the heights," in the "heavens." Here we discover a ready convergence of many elements and ideas: from this tree drips the nectar of immortality (soma or amrita) and whoever sips it is inspired with a vision beyond the reaches of time, a vision that awakens the memory of all the infinite forms of existence. In the foliage of the tree hides Yama, the god of beyond the grave, whom we also know as the king of the primordial state.

In Iran we also find the tradition of a double tree, one of which comprises, according to the Bundahesh, all seeds, while the other is capable of furnishing the drink of immortality (haoma) and spiritual knowledge, which leads us immediately to think again of the two biblical trees of Paradise, the one of Life, and the other of Knowledge. The first, then, is equivalent (Matt. 13:31-32) to the representation of the kingdom of heaven that sprouts from the seed irrigated by the man in the symbolical "field"; we encounter it again in the Apocalypse of John (22:2), and especially in the Qabalah as that "great and powerful Tree of Life" by which "Life is raised on high" and with which is connected a "sprinkling" by virtue of which is produced the resurrection of the "dead": a patent equivalence to the power of immortality in the Vedic amrita and Iranian haoma.

Assyro-Babylonian mythology also recognizes a "cosmic tree" rooted in Eridu, the "House of Profundity" or "House of Wisdom." But what is important to recognize in these traditions - because this element will be useful in what follows - is another association of symbols: the tree also represents for us the personification of the Divine Mother, of that same general type as those great Asiatic goddesses of Nature: Ishtar, Anat, Tammuz, Cybele, and so forth. We find, then, the idea of the feminine nature of the universal force represented by the tree. This idea is not only confirmed by the goddess consecrated to the Dodona oak - which, besides being a place of oracles, is also a fountain of spiritual knowledge - but also by the Hesperides who are charged with guarding the tree, whose fruit has the same symbolic value as the Golden Fleece and the same immortalizing power as that tree of the Irish legend of Mag Mell, also guarded by a femininte entity. In the Edda it is the goddess Idhunn who is charged with guarding the apples of immortality, while in the cosmic tree, Yggdrasil we again encounter the central symbol, rising before the fountain of Mimir (guarding it and reintroducing the symbol of the dragon at the root of the tree), which contains the principle of all wisdom. Finally, according to a Slavic saga, on the island of Bajun there is an oak guarded by a dragon (which we must associate with the biblical serpent, with the monsters of Jason's adventures, and with the garden of the Hesperides), that simultaneously is the residence of a feminine principle called "The Virgin of the Dawn."

Also rather interesting is the variation according to which the tree appears to us as the tree of dominion and of universal empire, such as we find in legends like those of Holger and Prester John, whom we have mentioned elsewhere. In these legends the Tree is often doubled - the Tree of the Sun and the Tree of the Moon.

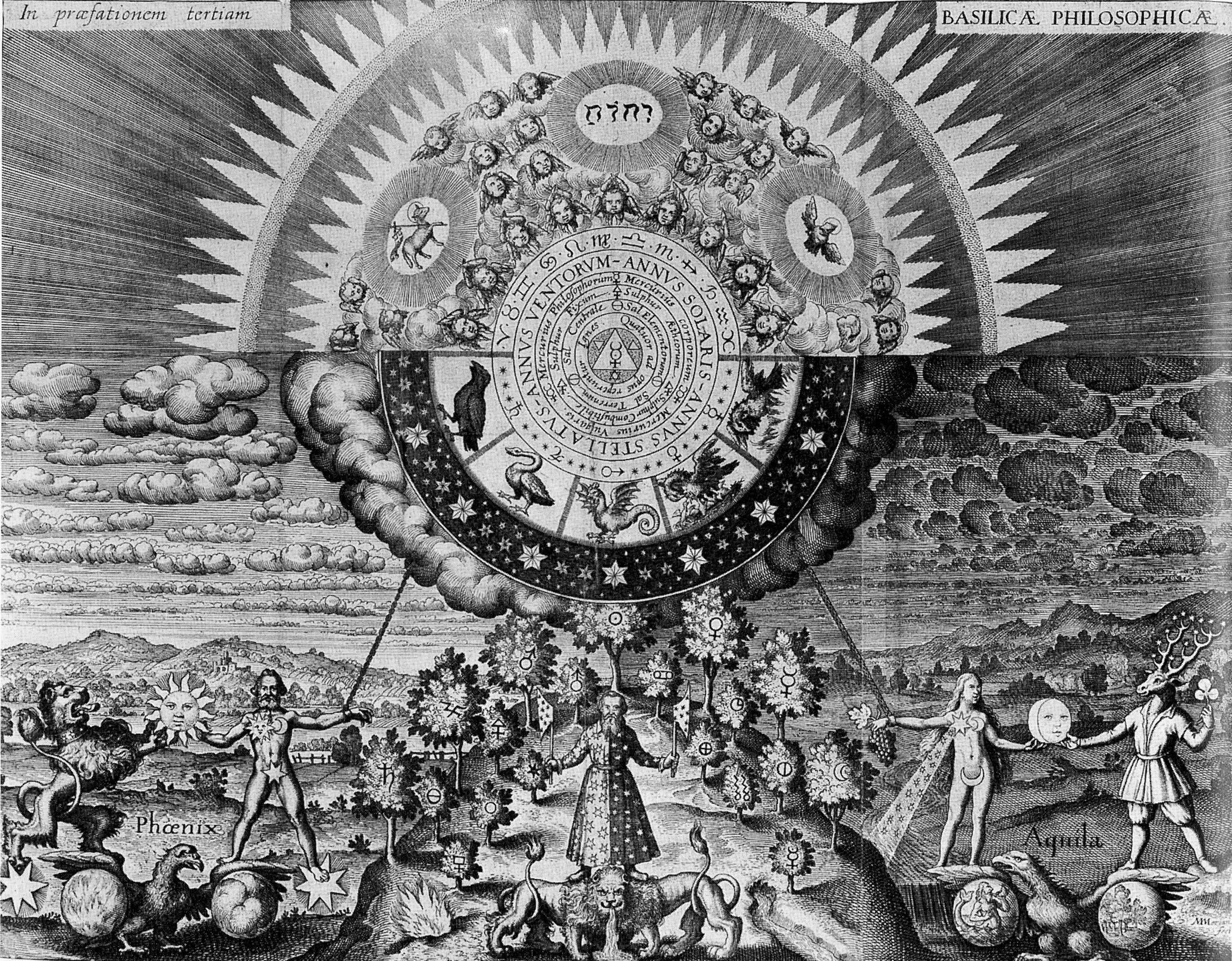

Hermeticism repeats the same primordial symbolic tradition and the same association of ideas, and the symbol of the tree is quite prevalent in alchemical texts. The tree shelters the "fountain of Bernard of Treviso, in whose center is the symbol of the dragon Ouroboros, who represents the"All" [footnote: In the cenral space of the tree is found the Phoenix, symbol of immortality, who brings us back to amrita and haoma]. It personifies "Mercury," either as the first principle of the hermetic Opus, equivalent to the divine Water or "Water of Life" that gives resurrection to the dead and illuminates the Sons of Hermes, or else it represents the "Lady of the Philosophers." But it also represents the Dragon, that is, a dissolving force, a power that kills. The Tree of the Sun and the Tree of the Moon are also hermetic symbols, sometimes producing crowns in the place of fruits.

This quick glance at the stuff of religion, which we could expand indefinitely, is enough to establish the permanence and universality of a tradition of vegetable symbolism expressing the universal force, predominantly in feminine form. This vegetable symbolism is the repository of a supernatural science, of a force capable of giving immortality and dominion, but at the same time warns of a multiple danger that complicates the myth in turn to various purposes, different truths and visions.

In general, the danger is the same anyone runs in seeking the conquest of immortality or enlightenment by contacting the universal force; the one who makes contact must be capable of withstanding overwhelming grandeur. But we also know myths in which there are heroes who confront the tree, and divine natures (in the Bible, God himself is hypostasized) that defend it and impede access to it. And the result, then, is a battle variously interpreted, according to the traditions.

There is a double possibility: in one case the tree in conceived as a temptation, which leads to ruin and damnation for anyone who succumbs to it; in the other, it is conceived as an object of possible conquest which, after dealing with the dragons or divine beings defending it, transforms the darer into a god and sometimes transfers the attributes of divinity or immortality from one race to another.

Thus, the knowledge that tempted Adam [ftnt: Although we shall return to the topic, let us pause for a moment to allow the reader to intuit the profound meaning of the symbol, according to which "temptation" is represented by "woman" - the "Living Eve" - who originally formed part of Adam] to "become as God" and that he attained only by immediately being knocked down and deprived of the Tree of Life by the very Being with whom he had hoped to equalize himself. Yet this is the same knowledge, supernatural after all, that the Buddha acquires under the tree, despite all the efforts of Mara, who, in another tradition, stole the lightning from Indra.

As chief of the Devas, Indra himself, in turn, had appropriated amrita from a lineage of anterior beings having characters sometimes divine and sometimes titanic: the Asuras, who with amrita had possessed the privilege of immortality. Equally successful were Odin (by means of hanging himself in self-sacrifice from the tree), Hercules, and Mithras, who after fashioning a symbolic cloak from the leaves of the Tree and eating its fruits, was able to dominate the Sun. In an ancient Italic myth, the King of the Woods, Nemi, husband of a goddess (tree=woman) had to be always on guard because his power and dignity would pass to whomever could seize and kill him. The spiritual achievement in the Hindu tradition is associated with cutting and felling the "Tree of Brahma" with the powerful ax of Wisdom.

The myth speaks to us of an event involving fundamental risk and fraught with elemental uncertainty. In Hesiod's theomachies, typically in the legend of the King of the Forest, gods or transcendental men are shown as possessors of a power that can be transmitted, together with the attribute of divinity, to whomever is capable of attaining it. In that case the primordial force has a feminine nature (tree =divine woman). It conveys the violence which, according to the Gospels is said to be necessary against the "Kingdom of Heaven." But among those who try it, those who are able to break through, triumph, while those who fail pay for their audacity by suffering the lethal effects of the same power they had hoped to win.

The interpretation of such an event brings to light the possibility of two opposing concepts: magical hero and religious saint. According to the first, the one who succumbs in the myth is but a being whose fortune and ability have not been equal to his courage. But according to the second concept, the religious one, the sense is quite different: in this case bad luck is transformed into blame, the heroic undertaking is a sacrilege and damned, not for having failed, but for itself. Adam is not a being who has failed where others triumph, he has sinned, and what happens to him is the only thing that can happen. All he can do is undo his sin by expiation, and above all by denying the impulse that led him on the enterprise in the first place. The idea that the conquered can think of revenge, or try to maintain the dignity that his act has confirmed, would seem from the "religious" point of view as the most incorrigible "Luciferism."

Comments

Post a Comment